I had planned to write about Ronald Knox and his (in)famous “Ten Commandments” of detective fiction for this week. Then, out of the blue, a student in my 17th century poetry class—in other words, completely unrelated to detective fiction!—asked me today about these very same Ten Commandments. Somehow, it seems like this post was meant to be!

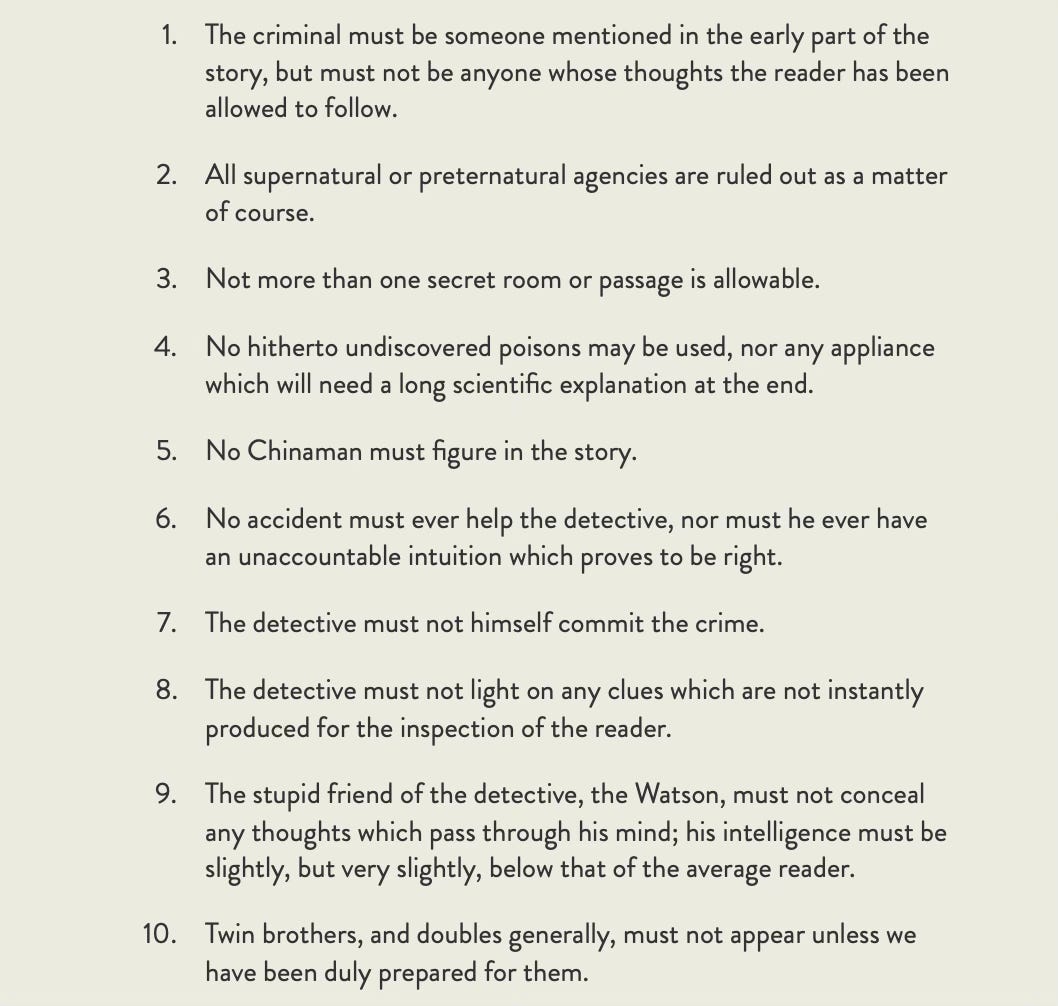

In case you don’t know what I’m talking about, let me explain that Ronald Knox was an Anglican priest in the early 1900s who also happened to be a writer and enthusiast of detective fiction. As Wikipedia explains, Knox is remembered for his “Ten Commandments”—otherwise also known as “Knox’s Decalogue”—“which sought to codify a form of crime fiction in which the reader may participate by attempting to find a solution to the mystery before the fictional detective reveals it.” So before further ado, here they are:

These “commandments” date back to 1928—all the way back to early Agatha Christie era—and what might strike first-time readers of Knox’s Decalogue is just how many of these rules have been broken not only in today’s detective fiction but even during Knox’s own time. Christie herself notoriously broke a couple of these rules (which will remain unidentified here) in her early famous novel Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926).

In my detective fiction classes, sometimes I teach Eulogy for a Brown Angel (2002) the first in the Gloria Damasco series by Chicana writer Lucia Corpi, and some students strongly object to the fact that the amateur detective protagonist sometimes experiences “visions” which partly guide her investigation. It almost seems that these students have taken to heart the commandments above and decided that Rule #2 (“All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course”) cannot be messed with!

When Rule #8 commands that all clues must be “instantly produced for the inspection of the reader,” what exactly does it mean to “produce” the said clue? After all, so many clues are often deliberately buried amongst other non-essential information.

Every time I see Rule #5 (“No Chinaman must figure in the story”), I cannot help thinking about the 12th entry in Ruth Rendell’s Inspector Wexford series, Speaker of Mandarin (1983), and wonder what she thought of her rule-breaking title. And what exactly are the distinguishing traits between an “unaccountable intuition” (Rule #6) and an accountable one?

But, of course, it’s important to remember that the British Golden Age writers and readers of detective fiction were particularly enthralled by the puzzle game aspect of the genre. If we were to map out a mystery novel on a giant board as if it were a game of Clue (or Cluedo in Britain where it originated in 1943), how might we establish the rules of engagement such that any careful reader-player could confidently assert: Colonel Mustard in the Conservatory with the Candlestick! (And then you realize that the game board’s four corner rooms have secret passageways, thus breaking Rule #3…)

Is there a particular rule you do NOT want your murder mystery to break? Do we have a different set of “rules” we abide by these days, or are most rules obsolete?

For me, I always try to avoid coincidences in my own work. (Perhaps partly number six?) It's too convenient and I've seen too many reviews where readers dislike coincidences. The detective just happens to see/hear something or encounter someone, etc. Perhaps one coincidence near the beginning is okay--the amateur detective happens to find the body or something along those lines--but too many just feels lazy on my part as the writer.

The rule to not allow the criminal to be anyone whose thoughts the reader has followed may be too limiting. I kind of like the unreliable narrator when it's done well and think maybe a criminal whose thoughts are somehow so muddied or self delusional as to not allow the reality of their crime to seep in to their thoughts might be a nice surprise to the reader. 😊